The Sopranos Season 2 Explained: How Sopranos Season 2 Stopped Being a Mob Show

Intro

When we talk about The Sopranos, the consensus is lazy.

We talk about the pilot. We talk about the finale. We talk about “Pine Barrens” and the masterful, brutal tension of Season 3’s “University.” We talk about the events. But we’re looking at the wrong frames. We’re missing the pivot.

As a filmmaker, I’m obsessed with the moment a story discovers what it’s really about.

Season 1 of The Sopranos was a brilliant high-concept. A mob boss goes to therapy. It’s a fantastic premise. It’s a great pilot. But it’s still, at its heart, a story bound by the rules of the genre. It’s about a man balancing two families.

Season 2 is where David Chase and his team threw the rulebook away. This is the season where the show stopped being a screenplay and started being a film. It’s where the visual grammar of the show shifted from the external to the internal. It’s not about what Tony does; it’s about what he fears.

It’s the turning point nobody talks about, and it’s the moment the show became a masterpiece.

A New Kind of Villain

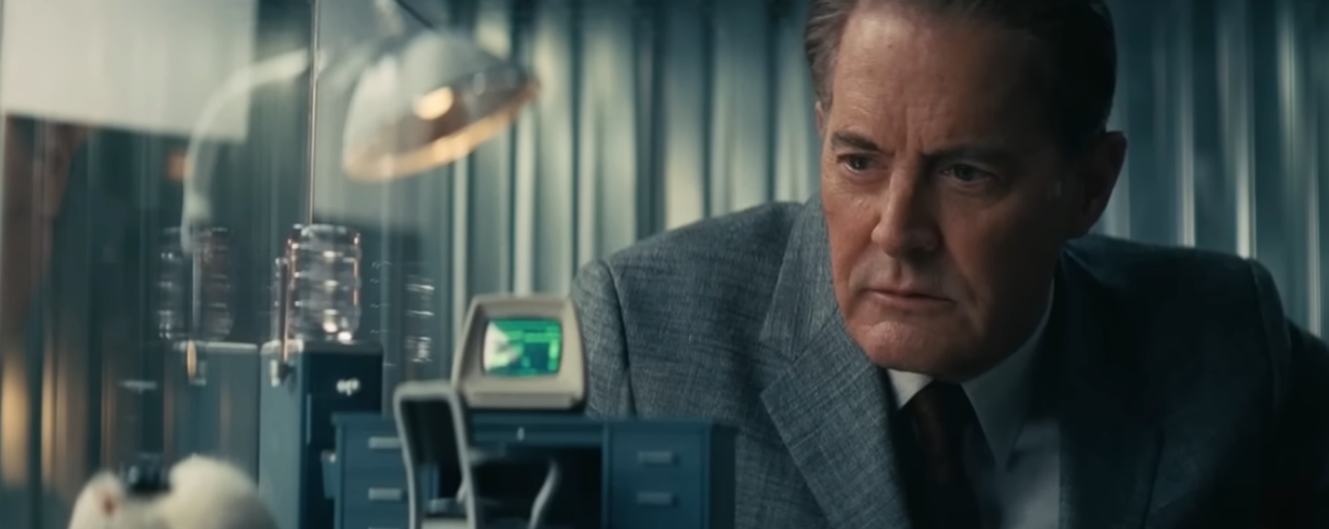

Look at our antagonist for the season. It’s Richie Aprile.

From a genre perspective, he’s a disaster. He’s not a calculating rival like a New York boss. He’s not a big bad. He’s a petty, insecure, small-minded dinosaur. He’s a man out of time, obsessed with his leather jacket and the respect he’s owed. He is, in a word, pathetic.

And that is the genius.

Chase gives us a villain who is not a threat to Tony’s business, but to his ego. Richie’s conflict isn’t about territory; it’s about domesticity. He moves into the house of the former boss. He challenges Tony at the dinner table. He’s the ghost of the past, and he’s an irritant.

How does this psychological threat get resolved? Not with a sit-down. Not with a garrote wire in a back alley.

It’s a domestic dispute. It’s a kitchen-floor execution.

The mise-en-scène isn’t a dark alley; it’s a cluttered kitchen counter. The weapon isn’t a .38; it’s a pistol retrieved from a cabinet. The aftermath isn’t a cinematic cleanup; it’s two amateurs arguing over how to use a butcher’s saw.

This is a choice. Chase takes the biggest mob event of the season and frames it as a pathetic, banal, domestic squabble. He’s screaming at us: The mob is not the point. The rot in the suburban home is the point.

📂Don’t just watch the show, analyze it. Grab Dr. Melfi’s confidential ‘Psychological Dossier’ on Tony (and the truth about the ending) here

The Subjective Camera: “I’m a Fish, Tony”

The most important storytelling decision of Season 2 is the Pussy storyline. But again, not for the reason you think.

A lesser show would frame this as a procedural. A spy thriller. Who is the rat?

The Sopranos doesn’t care. The real story, the one the camera is actually telling, is about Tony’s denial. It’s not a whodunnit; it’s a why-won’t-he-see-it.

How do you film denial? You can’t just write it in dialogue. You have to go inside.

This is the season the dream sequences become the show’s primary visual language. We’re not just watching Tony anymore; we are in his subconscious. The camera becomes subjective. The pacing becomes liquid.

The scene where Pussy, as a fish, speaks to Tony in a fever dream is the single most important moment in the show’s evolution. “You know who I am… We’re talking about you!”

This isn’t plot. This is pure, cinematic psychoanalysis. It’s Fellini in New Jersey. The show is telling us that the real story is happening in Tony’s psyche, not on the streets. Pussy isn’t just a rat; he is a literal, physical sickness. Look at him: he’s sweaty, he’s pale, he’s rotting from the inside. He’s the physical manifestation of Tony’s spiritual cancer.

The climax on the boat isn’t an execution. It’s an exorcism. It’s a mercy killing for Tony’s soul. When he sits in the boat’s wake, staring at the empty space, it’s not the look of a boss; it’s the look of a man who just cut a tumor out of his own gut.

Melfi & The McMansion

Finally, look at what the camera doesn’t show.

Season 2 is where the show falls in love with the empty frame. The long, lingering shots on the beige, empty rooms of the Soprano McMansion. The house is a character. It’s a mausoleum. It’s the physical manifestation of the spiritual void at the heart of the American dream.

This is the season Carmela stops being a “mob wife” and becomes a tragic figure. Her “B-plot”—her existential dread, her attempt to get a real estate license, her desperation for a future, isn’t a B-plot. It is the show.

At the same time, the Melfi scenes change. They’re no longer just exposition. They’re combat.

In Season 1, Melfi is a guide. In Season 2, she’s a prosecutor. This is the season she starts rejecting him. She calls him on his bullshit. The camera holds on Tony in the close-up, forcing us to sit in his discomfort. We watch him squirm. We watch him try to manipulate. The therapy room is no longer a safe space; it’s a crucible.

Season 1 built the set and introduced the characters. But Season 2 is when the camera stopped being a spectator and became a scalpel. It cut past the genre, past the mob-talk, and pointed straight at the rotten, hollow, and terrified soul of its protagonist. It’s not just great TV. It’s great cinema.

Post Comment