Meet Joe Black Movie Explained | How Meet Joe Black Made Death Romantic

How Meet Joe Black Made Death Romantic

Let’s be honest. In the pitch room, Death is a downer. It’s the end of the story, not the start. It’s a third-act complication, a box office liability. We dress it up, sure. We make it scary (horror), we make it sad (tragedy), we make it noble (war), or we make it a cheap plot point (the revenge flick). We’ll do anything, really, except invite it over for dinner.

Death is the ultimate antagonist. It’s the faceless, formless dread that hangs over every protagonist. It’s the Ingmar Bergman chess match on the beach; it’s the pale-faced, scythe-wielding specter.

And then, in 1998, along came a pitch that was so high-concept, so utterly audacious, it had no right to work: What if the Grim Reaper took a vacation? And what if, to do it, he took over the body of a devastatingly handsome young man? And what if… he was Brad Pitt?

Suddenly, Death wasn’t a liability. It was a romantic lead.

This is the central, brilliant con of Martin Brest’s Meet Joe Black. The film is a three-hour, high-gloss, impossibly lush meditation that pulls off the ultimate cinematic sleight of hand. It doesn’t just grapple with the philosophy of mortality; it grabs it, puts it in a bespoke suit, and makes us want to ask it for its number. It romanticized the end of all things, and it did so by using the oldest tricks in the Hollywood playbook.

The Casting Coup

The single most important decision in Meet Joe Black is its casting.

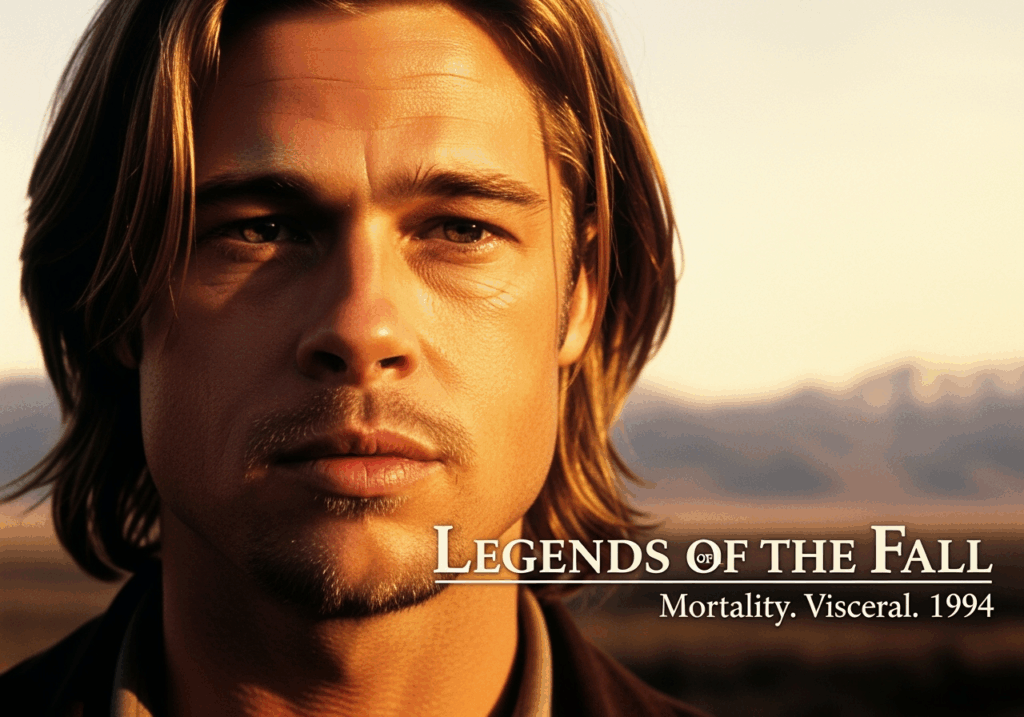

In 1998, Brad Pitt wasn’t just a star; he was the star. He was the golden-boy ideal, the sun-kissed romantic hero of Legends of the Fall. By taking the abstract concept of mortality and giving it that face, the film bypasses our intellectual defenses and goes straight for the visceral.

The genius is that the film doesn’t shy away from this. It leans in. When Susan Parrish (Claire Forlani) first meets the “Coffee Shop Guy” (the body Joe will soon inhabit), he is charming, nervous, and electric. Their chemistry is immediate. Then, he is violently killed in a now-infamous “peanut butter” scene.

When Death arrives at her father’s doorstep, he is wearing that man’s face, but he is fundamentally different. He’s a blank slate. He speaks slowly, his head tilted with a childlike curiosity. He is, quite literally, a “fish out of water”, a classic romantic-comedy trope.

And this is where the seduction begins. This “Joe Black” isn’t the wise, menacing reaper. He is innocent. He is experiencing the world for the first time, and that innocence makes him vulnerable. It’s this vulnerability, not his power, that makes him romantic. He’s discovering the taste of peanut butter with childlike glee. He’s baffled by human relationships. He’s a cosmic entity brought to his knees by the simple, overwhelming sensation of falling in love.

The film conflates the terror of the unknown with the thrill of a new romance. Susan isn’t just falling for a handsome stranger; she’s falling for the very concept of the end, and finding it to be gentle, curious, and utterly captivated by her.

The Other Love Story

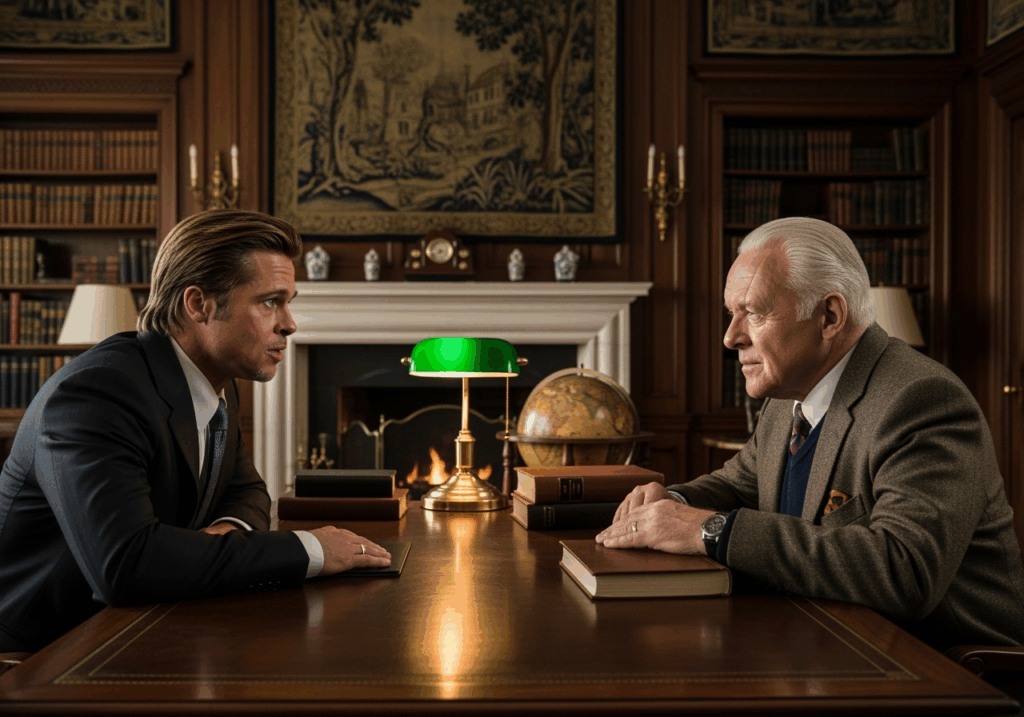

Of course, the central romance isn’t really between Joe and Susan. The true heart of the film, the machinery that makes the entire premise work, is the relationship between Joe and his “guide,” media mogul Bill Parrish (Anthony Hopkins).

This is where the philosophy gets its legs. The film posits Death not as a predator, but as a tourist. He’s not here to hunt; he’s here to learn. He wants to know why mortals cling so desperately to life. In exchange for a few extra days, Bill agrees to be his guide.

What follows is less a Faustian bargain and more a platonic love story between two titans. Hopkins, at the peak of his powers, imbues Bill with a weary, noble grace. He is a man who has built an empire, but now faces the one merger he can’t negotiate. He teaches Joe about loyalty, love, and legacy. In return, Joe, this naive god, offers Bill… an audience. He gives Bill a confidante for his deepest fears.

This is the film’s second trick. It reframes death not as a solitary void, but as a final, intimate conversation. Bill isn’t just dying; he’s being escorted. The climax of the film isn’t a tragic death; it’s a dignified departure. When Bill finally asks, “Should I be afraid?” Joe’s reply, “Not a man like you,” is the ultimate absolution.

The Hollywood Ending

For three hours, Meet Joe Black pulls off a high-wire act. It’s a slow, opulent, and deeply earnest film in an era that was trending toward the cynical. It’s a $90 million character study. And it works because it never flinches.

…Until the end.

In a final, perfect, and utterly “Hollywood” move, the film gives us everything. Joe, having learned his lesson about a love that is pure and selfless, cannot take Susan with him. He understands that to love her is to leave her. He and Bill walk off into a luminous mist, a gentleman’s exit.

But then, the music swells. And the “Coffee Shop Guy” walks back over the ridge.

Joe, in his final act, gives him back. He returns the vessel, presumably with no memory of being the Grim Reaper, allowing Susan to have her romance after all. It’s a “happily ever after” tacked onto an existential meditation.

And that is the final key to its romanticism. A truly European ending would have left Susan heartbroken, staring at the empty fireworks. But this is Hollywood. Meet Joe Black domesticates the abyss. It argues that death isn’t an end, but a transition. It suggests that not only is Death a gentleman who can be reasoned with, but he’s also a romantic who, after learning what it’s like to be human, might just do you a favor on his way out the door.

It’s a beautiful, preposterous, and impeccably crafted fantasy. It took the most terrifying concept known to man and turned it into a date movie. That’s not just philosophy. That’s magic.

Post Comment